At the end of 2017, I asked in a blog whether 2018 might be the next “Year of Revolutions”.

As is usually the case in journalism and blogging, a headline in the form of a question invites the answer “No”. But as we enter 2020, it is clear – as used to be said of the British Empire at the end of the 19th century – the sun never sets on countries and regions in turmoil.

In Western Europe we see the rise of nationalist and populist movements, the rise of demands for regional autonomy, and the rise of Green politics and protests. In the USA, politics has become vehemently partisan, and split on similar lines. In Russia’s cities, the educated young protest against the Putin regime, despite the threat of arrest and violence against them. In the Middle East, the Arab Spring remains unfinished business; additionally, religious factions seek dominance at the same time as social research suggests that young people in towns and cities are moving away from strict religious adherence.

In India there is conflict between an avowedly pro-Hindu Government and India’s 200 million-strong Muslim minority, who feel threatened and pushed to the margins. In China there are protests in Hong Kong, and, in the West, large-scale internment of Muslim Uighurs in “re-education” camps. Indonesia has seen protests in the cities against what is seen as Government corruption and indifference to hardship. The unprecedented scale and destructiveness of the Australian bush-fires seems likely to precipitate political protests and an invigorated Green movement, calling into question the scale of Australia’s economic reliance on coal.

In Africa and Latin America too there are protests across those two continents. Protests against economic mismanagement and corruption in Zimbabwe and South Africa; demands for greater autonomy in parts of Ethiopia – despite its impressive economic growth; wars of religion in and around the Sahel Regions; and tribal/ethnic conflicts in Central Africa and elsewhere. In Latin America, a left-wing Government has been ousted in Bolivia, while Venezuela’s holds power largely by main force alone; at the same time, Chile – the poster-child for centre-right liberal capitalism in the region – is under siege by its own disaffected citizens.

The causes I identified in the 2017 blog have not changed much: the continued fall-out of the financial crash, and the shift from “labour” to “capital”; the rise across the globe of populism, political polarisation and identity politics; a desire in democratic states for more local autonomy, and in undemocratic ones, for the right to freedom of expression and disgust with corruption, and governments that disregard the feelings and wishes of their people.

Some actual revolutions have happened, and will continue to happen. But it is perhaps more significant that a state of protest now seems to be “normal” in so many parts of the world. So this blog asks, whether this is a new status quo, or a transition to a different political settlement.

Precariousness of people’s lives certainly shows no sign of diminishing, and might well become more marked with the impact of the 4th industrial revolution on work, and the shifting tectonic plates of the balance of global economic power. In developing regions, urbanisation affords opportunities for association and protest that would have been largely denied to people in rural areas. In the developed world, cities are already the focus of most protest movements, and the pattern seems to be repeating in the developing cities of the 21st century. So the causes of protest seem to be here for the medium-term, and may even become more compelling. The megacities of the future – which are projected to be bigger by far even than today’s largest conurbations – may be even more volatile.

The nature and techniques of protest, and of Government responses to it, are evolving. The Arab Spring was heavily dependent on mobile technology and social media. You Tube and Twitter have brought protests to the attention of the world, through shared video clips. In Hong Kong, a population much of which is highly tech-savvy, has been innovative in its protests, for example the use of laser pens to “dazzle” the Government’s facial recognition equipment.

At the same time Governments, especially autocratic ones, are seeking to up their game on surveillance and identification techniques. China has been at the forefront of this, and is reported to have provided equipment to autocratic regimes overseas, for example Zimbabwe. Governments who are minded to do so can build up data over time on individuals, and mark them out for closer surveillance, and denial of opportunities, if not arrest and imprisonment. But they will not be able to do so in secret.

This “arms race” between Governments and protesters is not confined to the streets, of course, although that remains an important arena, and we can expect protest movements to resort to cyber sabotage and other measures to interrupt the normal workings of governments. The ubiquity of social media, and the growth of “unofficial” news media, means that protesters can present their case to the world.

The sheer size of the 21st century’s megacities would daunt the most oppressive governments. Lagos is projected to have a population of 88 million; Kinshasa 83 million; Dar-Es-Salaam 74 million; Mumbai 67 million; Delhi 57 million. It is not clear that governments would be able to control and contain such massive concentrations of humanity.

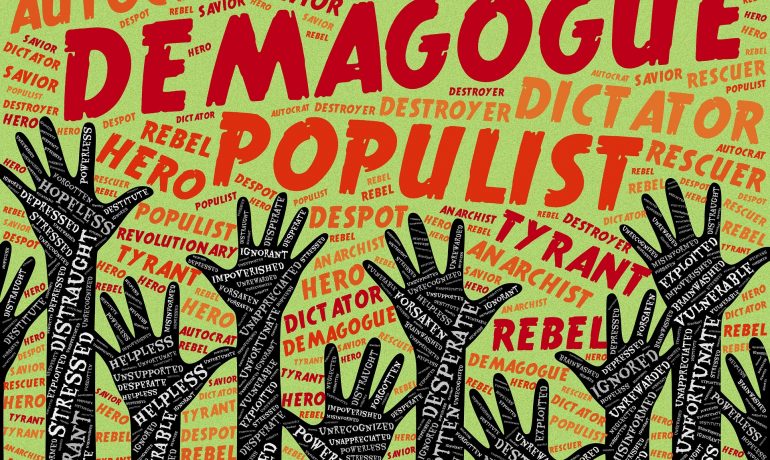

This “new normal” may create the conditions for more extreme and polarised politics. Rather than a political and economic establishment seeking consensus, as at the World Economic Forum, political careers may more easily be made by stepping outside the consensus and using the tools and techniques of protest to lead demands for radical change, appealing to the “teeming masses” in the megacities and – more worryingly – exploiting the divisions. Populism and demagoguery may become an established approach to politics.

Certainly the decline of the “soft” left and right in Western democratic politics suggests that it is becoming harder for the politics of consensus to get a hearing in a noisy and tumultuous world.

One thing may work as a force for relative stability: the aging population. By 2050 the average age of the population of Europe will be 45; in Japan and South Korea, it will be over 50, and even in China, it will be in the 40s. Perhaps protest is a young person’s thing. In which case street politics will play out most dramatically in Africa and India, while the rest of us will decide we all need to calm down. Watch this space….

Written by David Lye, SAMI Fellow

The views expressed are those of the author and not necessarily of SAMI Consulting.

SAMI Consulting was founded in 1989 by Shell and St Andrews University. They have undertaken scenario planning projects for a wide range of UK and international organisations. Their core skill is providing the link between futures research and strategy.

If you enjoyed this blog from SAMI Consulting, the home of scenario planning, please sign up for our monthly newsletter at newreader@samiconsulting.co.uk and/or browse our website at http://www.samiconsulting.co.uk